8 Reasons Why Cats Pant in a Car — Causes, What to Do & When to Worry

Last Updated on October 9, 2025

Seeing a cat pant in a car unsettles any owner. Because panting is rare in cats, car rides can reveal stress, overheating, motion sickness, or illness. Spotting true panting—not the brief Flehmen response—guides the next move.

This post breaks down eight causes of cat panting in a car, the immediate steps to take, and when to worry. It also covers quick checks like gum color and breathing effort, plus prevention tips for cooler cabins, calmer carriers, and safer trips.

How to recognize panting in a car

8 Reasons Why Cats Pant in a Car — Causes, What to Do & When to Worry: owners must tell true panting from other mouth behaviors while traveling. Panting in cats looks like rapid, open-mouth breathing with visible tongue movement and an increased respiratory rate. It often comes with flattened ears, dilated pupils, and a tense body. Note the duration and triggers—short, transient breaths after a stressful event differ from continuous panting.

If a cat pants in a car, observe breathing rhythm, effort, and color of gums. Pale, blue, or very red gums suggest poor oxygenation or heatstroke and require urgent attention. Light, infrequent open-mouth breathing immediately after intense stress may resolve quickly once the environment calms.

For tips to calm a cat and reduce travel-related breathing changes, see how to calm down a cat in the car.

What cat panting looks and sounds like (vs. Flehmen response)

Panting sounds like quick, shallow pants or continuous rapid breaths with audible airflow. Cats may exhale harder than they inhale. The Flehmen response looks different: the cat curls back its upper lip, breathes through the mouth briefly, then closes it. Flehmen is brief and investigative. Panting persists, involves visible effort, and lacks the lip-curling posture of Flehmen.

Why panting in cats is less common — when it’s normal vs. abnormal

Cats rely on grooming, vasodilation, and behavior to cool down. They pant less because those methods usually suffice. Normal panting is rare, short-lived, and follows intense exertion or brief extreme stress. Abnormal panting lasts longer, worsens with movement, or appears with vomiting, collapse, or altered mentation. These signs demand immediate veterinary care. As a rule, if panting does not stop when the environment cools and the cat calms, seek emergency help.

8 common reasons cats pant during car rides

Cats panting in a car signals several possible issues, from simple stress to life-threatening conditions. Each cause has distinct signs and specific immediate steps owners should take. The following subsections break down common reasons, how to tell them apart, what to do right away, and when to seek emergency care.

Stress, fear and travel anxiety — carrier and vet associations

Many cats pant from acute anxiety during travel. Panting may accompany wide eyes, flattened ears, vocalization, trembling, drooling, or attempts to hide. Owners should first ensure the carrier is secure, padded, and positioned to limit motion and visual stimuli. Short acclimation trips and pheromone spray help. For calming techniques and stepwise desensitization, see How to calm down a cat in the car. If panting persists with collapse, disorientation, or pale gums, seek veterinary care immediately.

Overheating or poor ventilation inside the vehicle

Heat stress causes rapid, open-mouth breathing that can escalate to heatstroke. Signs include excessive drooling, bright red gums, weakness, vomiting, or collapse. Owners should stop the car, move the cat to shade, and offer cool (not cold) water. Increase ventilation or use air conditioning; never leave a cat unattended in a parked vehicle. For tips on safe vehicle environments and ventilation when traveling long distances, consult guidance on traveling with cats in an RV.

Motion sickness or nausea from movement

Motion sickness produces panting accompanied by lip-licking, drooling, yawning, and sometimes vomiting. Younger and anxious cats show it more often. Preventive strategies include fasting a few hours before travel and providing secure, low-motion carriers. Veterinarians can prescribe anti-nausea medication for frequent travelers. For practical suggestions to reduce motion-sickness behaviors, review techniques used for motion-sensitive pets like in No More Doggie Dramas; many tips transfer to cats.

Respiratory problems (asthma, infection, pneumonia)

Respiratory disease produces rapid breathing, open-mouth panting, wheeze-like sounds, coughing, or nasal discharge. Cats with chronic asthma may pant episodically, while infections often bring fever and lethargy. Owners should stop driving and keep the cat calm and upright. Avoid aerosols or smoke exposure. Because respiratory distress can deteriorate quickly, contact a veterinarian promptly for evaluation and oxygen therapy if needed.

Heart-related issues and fluid around the lungs

Heart disease or pulmonary edema reduces oxygenation, causing heavy panting, weakness, fainting, and pale or bluish gums. These cats may also cough and show abdominal breathing. Transport the cat to an emergency clinic immediately. While en route, minimize handling and keep the cat warm and upright. Prompt diagnostic imaging and cardiac treatment can be lifesaving.

Acute pain or recent injury

Acute pain from trauma, fractures, or internal injury leads to rapid panting with vocalizing, guarding, or reluctance to move. Owners who suspect recent injury should stabilize the cat gently in a carrier and avoid unnecessary manipulation. Follow safe lifting practices to prevent further harm—see techniques for lifting and loading animals in 5 Steps to Safely Lift a Large Dog Into a Car, which apply to careful, two-person lifts for injured cats. Seek immediate veterinary attention.

Partial airway obstruction or inhaled/ingested object

An obstructed airway causes noisy panting, coughing, pawing at the mouth, drooling, and sudden distress. Open-mouth breathing with collapse indicates a severe blockage. If the object is visible and removable without force, a gloved owner may attempt careful extraction. Otherwise, transport the cat upright to an emergency clinic immediately. Secure the carrier to prevent escape. Preventive measures include securing small items and ensuring carriers close properly; see tips on carrier safety at How to secure a cat carrier in car.

Anemia or other systemic illnesses reducing oxygen delivery

Anemia, sepsis, or metabolic disease can cause panting because tissues receive less oxygen. Look for pale gums, lethargy, rapid heartbeat, or weight loss. These conditions often produce subtle signs before a crisis. Owners should avoid exertion and arrange urgent veterinary evaluation, where bloodwork and supportive oxygen therapy clarify diagnosis and treatment. If a cat shows progressive weakness with panting, contact a veterinarian or emergency clinic without delay.

Signs that panting is an emergency

Panting in a cat during a car ride can range from stress to life-threatening distress. Emergency-level panting usually looks extreme and lasts longer than a minute or two. Key indicators include very rapid breath rate (well above normal resting rates), open-mouth breathing that sounds noisy or strained, and persistent heavy salivation or vomiting. Other urgent signs include pale, blue, or brick-red gums, sudden collapse, seizure activity, or an inability to stand.

When any of these appear, the driver should stop the car safely and call the veterinarian or emergency clinic immediately. Keep the cat contained and still inside its carrier if possible; sudden extraction can increase injury or cause escape. Move the vehicle to a shaded, cool spot and allow fresh air to reach the cat without forcing contact. Time respiratory rate and note changes—this information speeds triage at the clinic.

If the cat’s condition deteriorates rapidly, seek emergency care rather than attempting home treatments. For non-life-threatening anxiety-driven panting, consult practical calming techniques for travel, such as those outlined at how to calm down a cat in the car.

Concerning physical cues (gums, color, collapse, prolonged noisy breathing)

Physical signs reveal oxygenation and circulation problems quickly. Healthy gums are pink and moist. Pale or white gums suggest poor circulation or shock. Blue or purple gums indicate hypoxia—insufficient oxygen in the blood. Brick-red gums can signal heatstroke or sepsis. Any sudden change in gum color with panting demands urgent veterinary assessment.

Collapse or loss of coordination signals systemic failure or severe respiratory compromise. Prolonged noisy breathing—wheezing, stridor, or harsh raspy sounds—may mean airway obstruction, laryngeal spasm, or fluid in the lungs. These conditions can progress fast and require oxygen therapy and diagnostics.

If it’s safe, open carrier vents to improve airflow, but avoid pulling a frightened cat from its carrier unless evacuation is essential. Secure the carrier before travel to reduce injury risk; see practical tips on how to secure a cat carrier in car for prevention strategies that lower emergency chances.

When panting comes with other red flags (coughing, gagging, weakness)

Panting coupled with respiratory sounds, coughing, or gagging narrows likely causes toward airway disease, aspiration, or cardiac problems. Coughing or retching during panting may indicate aspiration of food, vomit, or car-sourced irritants. Aspiration risks pneumonia, which often worsens over hours to days and needs veterinary antibiotics and support.

Generalized weakness, stumbling, or tremors alongside panting suggest systemic illness: toxin exposure, severe dehydration, metabolic crisis, or heart failure. Heart disease can present as rapid breathing, weakness, and coughing due to pulmonary edema. Allergic reactions also cause panting plus gagging and can escalate to anaphylaxis.

Do not give oral fluids or medications without veterinary advice. Prepare to transport the cat in its carrier, bring a clear timeline of symptom onset, and report any exposure risks. For owners managing travel-prone cats, refer to guidelines on handling difficult travelers at how to travel with a fussy feline. Call a vet immediately when red flags appear; early intervention improves outcomes.

Immediate steps to help your cat in the car

When a cat pants in a car, quick, calm action reduces risk. The owner should assess breathing, temperature, and behavior without startling the cat. Move through the checks in order: cool, hydrate, and soothe. If panting started during a long drive or in warm weather, treat it as potentially urgent.

Safe moves to cool and calm them (AC, water, shade, carrier positioning)

Turn the air conditioning on or direct vents toward the carrier to lower cabin temperature. Park in shade and switch off the engine only if safe to do so. Offer small amounts of cool water with a syringe or shallow dish; avoid forcing the cat to drink. Position the carrier so it sits flat and stable, with the door facing away from strong drafts to reduce stress. A damp towel over the carrier roof helps lower heat without blocking airflow. Never apply ice directly to the cat’s body.

Simple calming tools you can use right away (pheromones, quiet stops, treats)

Use a synthetic feline pheromone spray or diffuser to reduce stress; spray the carrier exterior briefly. Make quiet stops to let the cat settle inside the vehicle rather than at busy locations. Offer a few tiny, familiar treats to encourage slow breathing. A familiar blanket or toy inside the carrier reduces visual stress. For more strategies on keeping a cat calm in transit, consult the guide on how to calm down a cat in the car.

When to pull over and call your veterinarian or emergency clinic

Pull over and call a vet if panting persists after cooling for 10–15 minutes, or if the cat shows pale or blue gums, drooling, vomiting, collapse, or severe disorientation. Rapid heart rate, unresponsiveness, or seizures require immediate emergency care. Inform the clinic of heat-related symptoms and follow phone instructions. Do not give human medications or attempt invasive treatments without veterinary guidance. If urgent care is needed, a prompt call can save time and lives.

How veterinarians diagnose panting causes

When a cat pants in a car, veterinarians follow a structured approach to identify the cause. They begin with a focused history: when panting started, duration, exposure to heat, medications, recent travel, and any known medical conditions. A veterinarian observes the cat’s respiratory pattern, effort, and behavior. They record vital signs, including temperature, heart rate, and mucous membrane color. These baseline data help distinguish routine stress from life‑threatening problems such as heatstroke, respiratory obstruction, or cardiac failure. The clinician then decides which immediate interventions are needed, such as cooling, oxygen, or anxiolytics, and whether urgent transport to a clinic is required. If panting appears linked to travel stress, securing the carrier and reducing motion triggers can help on subsequent trips; see practical tips for restraint and safety at How to secure a cat carrier in car. Quick recognition and targeted testing shorten diagnostic time. If signs point to a serious disorder, the veterinarian proceeds to the tests described below.

Key exams and tests (physical exam, bloodwork, pulse oximetry, X‑rays)

The physical exam is the cornerstone. A veterinarian assesses respiratory rate and effort, listens to the lungs and heart, and checks chest wall symmetry. They inspect mucous membranes and capillary refill time for perfusion abnormalities. Pulse oximetry provides rapid, noninvasive oxygen saturation readings and detects hypoxemia that warrants immediate oxygen therapy. Routine bloodwork commonly includes a complete blood count and biochemical panel. These tests reveal infection, anemia, metabolic imbalances, or toxin exposure that can cause panting. Blood glucose and thyroid testing fit specific clinical suspicions. Thoracic radiographs (X‑rays) evaluate the lungs, heart size, and pleural space. Radiographs can show pneumonia, pulmonary edema, masses, or traumatic injuries. Where stress or pain likely precipitated panting, mild sedation during exam can yield more accurate findings. Results from these key tests direct treatment. Pet owners should seek veterinary care promptly if panting is persistent, labored, or accompanied by vomiting, collapse, or blue gums. For owners needing behavioral tips to reduce travel stress, consult How to calm down a cat in the car.

Advanced diagnostics for chronic or unclear cases (echocardiogram, chest imaging)

If initial testing does not reveal a cause, or if panting recurs, veterinarians escalate to advanced diagnostics. An echocardiogram provides real‑time assessment of heart structure and function. It identifies cardiomyopathies, valvular disease, and pericardial effusion that can present with respiratory signs. Advanced chest imaging, such as computed tomography (CT) or ultrasound, offers higher resolution views of lung parenchyma, mediastinum, and pleura. CT can detect small masses, bronchial collapse, or interstitial lung disease missed on X‑rays. Bronchoscopy allows direct visualization and sampling from airways when infection or inflammatory disease is suspected. Arterial blood gas analysis quantifies oxygenation and acid‑base status for complex respiratory compromise. Referral to a veterinary cardiologist or internal medicine specialist often improves diagnostic yield and management. For cats whose panting ties to chronic travel anxiety or repeated trips, coordinate advanced workups with behavior modification plans like those outlined in How to travel with a fussy feline. Owners should ask their veterinarian about referral and the expected timeline for tests and treatment.

Typical treatments based on cause

Treatment for a cat that pants in a car depends on the underlying cause identified by the veterinarian. Owners should remember the title 8 Reasons Why Cats Pant in a Car — Causes, What to Do & When to Worry when deciding how urgently to act. Mild stress needs different care than respiratory obstruction, heart failure, or heatstroke. The sections below outline common immediate and follow-up interventions.

Short-term emergency care (oxygen, IV fluids, removal of foreign body)

When panting accompanies collapse, blue gums, severe difficulty breathing, or overheating, the situation becomes an emergency. The first step is to stop the car, move the cat to shade or a cool area, and call a vet.

At the clinic, staff may provide oxygen therapy in a mask or oxygen cage to improve oxygenation. Veterinarians often start IV fluids for shock or heatstroke to restore circulation and lower body temperature. If a foreign object blocks the airway, clinicians perform removal under sedation or general anesthesia and secure the airway by intubation if needed.

Ongoing management options (inhalers for asthma, heart meds, transfusions)

For chronic respiratory or cardiac causes, vets prescribe long-term therapies. Feline asthma commonly responds to inhaled corticosteroids and bronchodilators delivered via a spacer and mask. Heart disease treatment may include diuretics, ACE inhibitors, or drugs like pimobendan to improve cardiac output and reduce fluid buildup.

Severe anemia from trauma or hemolysis may require blood transfusions and diagnostics to find the cause. Owners should expect follow-up imaging, bloodwork, and a clear medication plan. Regular rechecks help adjust doses and avoid recurrent panting episodes.

Motion sickness and anxiety interventions (medications and behavioral plans)

When panting stems from motion sickness or acute anxiety, combine medication and behavior change. Short-term prescriptions such as antiemetics or sedatives can control nausea and extreme stress before travel. Commonly used drugs include anti-nausea medications and, in some cases, low-dose anxiolytics prescribed by a veterinarian.

Behavioral plans include crate training, calming pheromones, gradual desensitization with short practice trips, and counterconditioning using treats or play. For practical guidance on calming a cat during car travel, see how to calm down a cat in the car. If panting continues despite these measures, contact the veterinarian or an emergency clinic immediately.

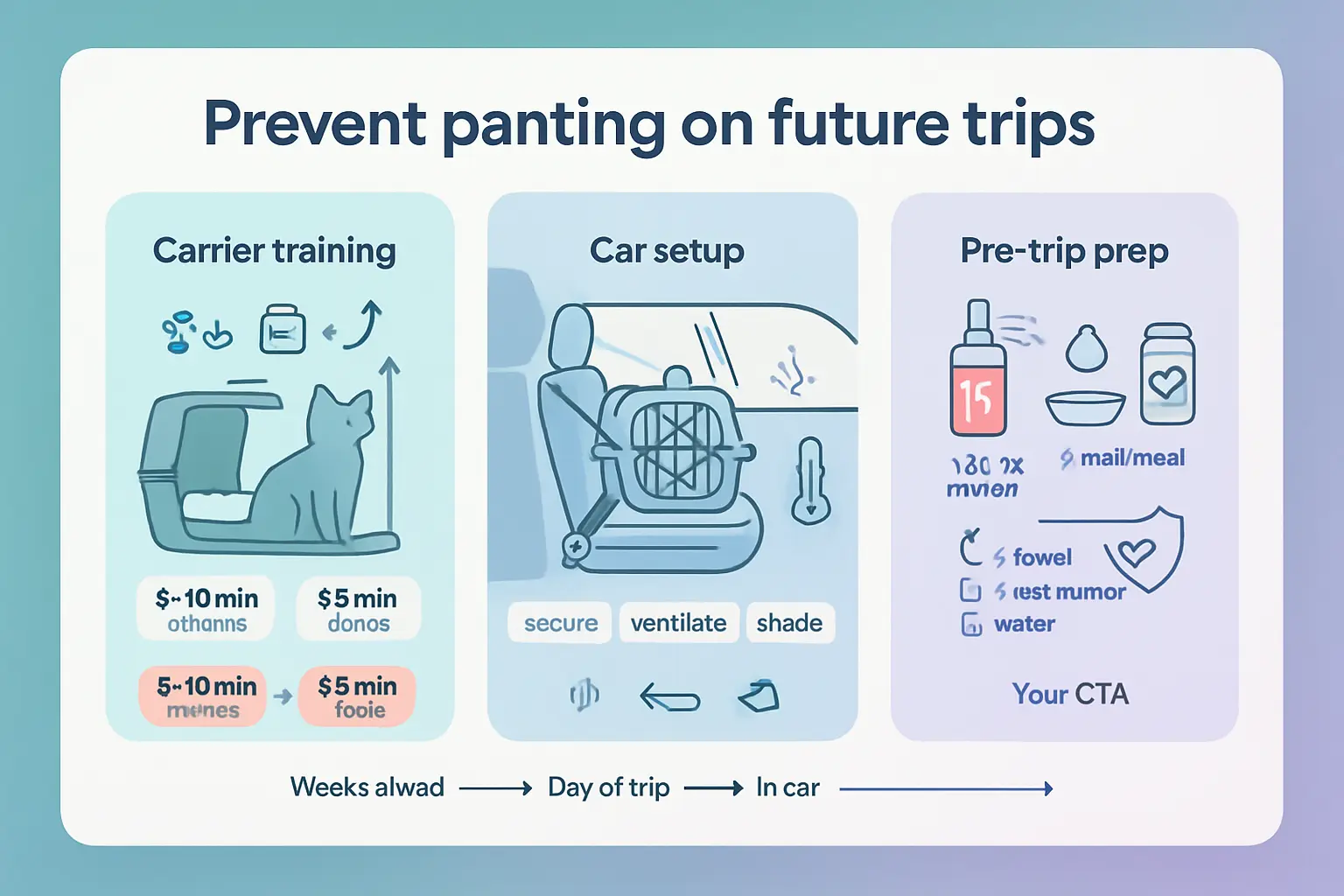

How to prevent panting on future trips

Owners reduce panting most effectively by treating travel as a skill to teach, not a one-off problem. Three consistent strategies work together: carrier and desensitization training, an optimized car setup, and smart pre-trip measures such as pheromones or medications when needed. Start weeks before long journeys and progress in short, measurable steps. Record the cat’s responses and stop if signs of panic appear. Use reward-based training: play, treats, and calm praise after successful short sessions. Rotate these sessions with quiet time in the carrier so the cat learns rest, not only travel.

Testing the whole routine in short drives is crucial; build distance and duration gradually until the cat breathes normally. For detailed tactics on calming a reluctant traveler and stepwise desensitization, see How to travel with a fussy feline. Keep a travel checklist: carrier, calming aids, water, a towel with home scent, and the vet’s emergency number. If panting recurs despite prevention, document when it happens and consult the veterinarian before the next trip.

Carrier training and short desensitization drives

Effective carrier training follows predictable, short sessions that pair the carrier with positive experiences. Leave the carrier out at home with soft bedding and treats. Feed meals near, then inside, until the cat enters voluntarily. Gradually close the door for a few seconds, increasing time over days.

Once the cat accepts the carrier at home, introduce the car. Start with the carrier in the parked car with the engine off for 5–10 minutes, then try the engine on for a minute. Progress to short drives under five minutes. Reward calm behavior immediately after exiting the car to link rides with positive outcomes. Keep sessions consistent—daily or every other day—and never force a cat into a carrier, which increases fear.

Desensitization should end each session before the cat shows stress signals. If panting begins, stop and return to a shorter, easier step the next session. For more calming techniques specifically for car travel, consult How to calm down a cat in the car.

Car setup tips (ventilation, cooling pads, position and visibility)

A stable, well-ventilated cabin prevents overheating and reduces stress. Place the carrier on the rear seat or floor behind a secure seat, where movement feels less intense. Secure the carrier so it cannot slide; use seat belts or anchor straps to minimize rocking. Avoid placing the carrier in direct sunlight; use window shades or a light towel to reduce glare but keep airflow unobstructed.

Maintain a comfortable temperature: running the air conditioning or cracking a window helps. Add a cooling pad or frozen water bottle wrapped in a towel for hot days. Choose a carrier size that allows the cat to turn and lie down, but not so large that it slides. Keep the carrier door secure yet visible to the cat; some cats calm when they can see a familiar person, while others prefer opaque sides—test which the cat prefers during short drives.

Soft bedding and an item with home scent reduce anxiety. For guidance on correctly securing carriers in vehicles, see How to secure a cat carrier in car.

Pre-trip options: pheromones, vet-prescribed meds, timing and hydration

Pre-trip preparation reduces acute panting triggers. Start with non-drug options: synthetic feline pheromone sprays or wipes applied to bedding and the carrier about 15–30 minutes before travel. Test pheromones at home first to confirm a calming effect. Offer a small meal a few hours before travel rather than immediately before, to avoid nausea, and ensure access to fresh water until departure to prevent dehydration.

If behavior remains severe, consult a veterinarian about short-term medications. Commonly prescribed options include gabapentin or trazodone; dosing and timing vary by weight and individual health. Never medicate without veterinary guidance. Trial doses at home well before a trip to monitor side effects and effectiveness. Natural supplements—l-theanine, fish oil, or herbal blends—help some cats, but evidence varies; discuss choices with the vet.

Document responses and adjust the plan accordingly. When in doubt about dosing or severe panting, contact the veterinarian immediately. For additional ideas on natural travel remedies and calming aides, review 9 natural ways to remedy travel anxiety.

Quick emergency checklist and common FAQs

A sudden panting episode in the car deserves quick, focused action. First, prioritize the cat’s airway, breathing and temperature. Remain calm; a stressed caregiver increases a cat’s anxiety and can worsen panting. Keep tools within reach: a towel, water, a carrier that can open on one side, and your veterinarian’s phone number. If the cat shows collapse, severe disorientation, or seizures, treat this as an emergency and seek veterinary care immediately.

For travel-related anxiety and practical calming techniques that reduce panting risk on future trips, consult resources on how to calm down a cat during car rides. How to calm down a cat in the car offers behavior-based tips owners can apply before and during travel.

Quick reminders:

- Do not force water into the cat’s mouth; allow voluntary drinking.

- Avoid human medications unless a vet prescribes them.

- Transport the cat to a cool, quiet environment promptly if heat or severe stress is suspected.

One-minute checklist for a panting cat in the car

When panting starts, act within the first minute to reduce risk. Follow these steps in order:

- Pull over safely and park in shade.

- Turn on the car’s AC or open windows to increase airflow.

- Keep the cat secured. If inside a carrier, open the carrier’s door or top just enough to improve ventilation while preventing escape.

- Offer small amounts of cool water. If the cat refuses, do not force it.

- Apply a cool, damp towel to the cat’s paws and neck—avoid ice-cold water on large areas.

- Watch the cat’s breathing rate and effort; note color of gums (pale, bright red, or blue are concerning).

If breathing remains rapid or worsens, drive directly to the nearest emergency veterinary clinic. For tips on safely keeping carriers secure while allowing quick access during travel, see guidance about securing a cat carrier in the car. How to secure a cat carrier in car

Short answers: “Is this normal?”, “Can cats get heatstroke?”, “When to give meds?”

Is this normal? Occasional panting can result from acute stress, motion discomfort, or brief exertion. Persistent panting, open-mouth breathing at rest, or panting paired with lethargy, drooling, or vomiting is not normal and needs veterinary assessment.

Can cats get heatstroke? Yes. Cats tolerate heat poorly. Enclosed cars heat rapidly. Signs of heatstroke include collapsed or very weak behavior, bright red gums, excessive drooling, vomiting, disorientation, and seizures. Heatstroke is life-threatening and requires immediate cooling and veterinary care.

When to give meds? Only administer medications prescribed by a veterinarian. Never give human anti-anxiety drugs, sedatives or painkillers without veterinary direction. For recurrent travel anxiety or motion sickness, a vet can recommend pre-trip antiemetics or anxiolytics and provide dosing tailored to the cat’s weight and health. For practical travel-prep strategies and when to discuss medications with a vet, review travel-focused guidance such as How to travel with a fussy feline.

CTA: If uncertainty remains, call the vet now. Clear, immediate guidance can prevent deterioration.

Summary

“8 Reasons Why Cats Pant in a Car — Causes, What to Do & When to Worry” explains how to recognize true panting, distinguish it from the Flehmen response, and identify what’s normal versus abnormal. It outlines eight common causes—stress, overheating, motion sickness, respiratory disease, heart issues, pain, airway obstruction, and systemic illness—and the exact steps owners should take immediately, plus clear red flags that demand emergency care.

The guide also covers how veterinarians diagnose the cause, typical treatments, and proven prevention strategies for future trips. With practical checklists and calming tools, owners can act fast, know when to seek urgent help, and build a safer, calmer travel routine for their cats.

Key Takeaways

- Confirm it’s panting: rapid, open‑mouth breaths with tongue movement and visible effort; not the brief, lip-curling Flehmen response.

- Scan for emergencies: pale/blue or brick‑red gums, collapse, severe lethargy, noisy or labored breathing, persistent vomiting—seek immediate veterinary care.

- Act right away in the car: pull over, cool the cabin, improve airflow, keep the cat secured, offer small amounts of cool water, and monitor breathing and gum color.

- Match action to cause: anxiety and motion sickness respond to calming, secure carriers, and vet‑prescribed meds; respiratory, cardiac, heatstroke, trauma, or obstruction require urgent treatment.

- Prevent future episodes: carrier training, short desensitization drives, temperature and ventilation control, secure positioning, pheromones, and pre‑trip vet guidance.

- Don’t improvise meds: avoid human drugs and forced fluids; follow a veterinarian’s instructions only.

FAQ

- What does cat panting in a car look like versus a Flehmen response? Panting is sustained, open‑mouth, rapid breathing with effort and tongue movement. The Flehmen response is brief, with a lip curl and mouth slightly open for a moment, then normal breathing resumes.

- Why do cats pant during car rides? Common reasons include acute stress, heat or poor ventilation, motion sickness, respiratory or heart disease, pain or injury, airway obstruction, and illnesses like anemia that reduce oxygen delivery.

- How should an owner help a panting cat immediately? Pull over safely, lower the cabin temperature, increase airflow, keep the cat secured, offer small amounts of cool water, and watch breathing effort and gum color. If panting persists or red flags appear, call a veterinarian.

- When should panting be treated as an emergency? Treat it as urgent with pale/blue or brick‑red gums, collapse, severe weakness, continuous noisy breathing, repeated vomiting, seizures, or panting that doesn’t ease after cooling for 10–15 minutes.

- How can panting be prevented on future trips? Use gradual carrier and car desensitization, secure and stabilize the carrier, optimize ventilation and temperature, and consider pheromones or vet‑prescribed anti‑nausea/anxiety meds after a trial at home.